Crystal Field Theory was developed to describe important properties of complexes (magnetism, absorption spectra, oxidation states, coordination,). The basis of the model is the interaction of d-orbitals of a central atom with ligands, which are considered as point charges. According to CFT, the attraction between the central metal and ligands in a complex is purely electrostatic.

The theory is developed by considering energy changes of the five degenerate d- orbitals being surrounded by an array of point charges consisting of the ligands. As a ligand approaches the metal ion, the electrons from the ligand will be closer to some of the d-orbitals and farther away from others, causing a loss of degeneracy. The electrons in the d-orbitals and those in the ligand repel each other due to repulsion between like charges. Thus, the d-electrons closer to the ligands will have a higher energy than those further away, which results in the d-orbitals splitting in energy.

This splitting is affected by the following factors:

• The nature of the ligands. The stronger the ligand, the greater is the splitting.

• Oxidation state of the central metal ion. A higher oxidation state leads to larger splitting.

• Size of d orbitals (i.e., transition series).

• Geometry of the complex.

Orbital Splitting:

The five d-orbitals are given the symbols dxy, dzx, dyz, dx2-y2 and dz2. In a complex they are all differently aligned relative to the incoming charge. Depending on the geometry of the complex, some of the d-orbitals will point directly towards the ligands, while some will point between them. Those which point at the ligands will experience more repulsion between their own electrons and those of the incoming ligands, than will those which do not point directly at them. Thus, the orbitals pointing at the ligands will be less stable and higher in energy. Now all the d-orbitals are no longer equivalent, giving rise to the phenomenon of orbital splitting, and the difference in energy between the more and less repelled orbitals is called the crystal field splitting parameter.

For example, consider a molecule with octahedral geometry. Ligands approach the metal ion along the x, y, and z axes. Therefore, the electrons in the dz2 and dx2−y2 orbitals (which lie along these axes) experience greater repulsion. It requires more energy to have an electron in these orbitals than it would to put an electron in one of the other orbitals. This causes a splitting in the energy levels of the d-orbitals. This is known as crystal field splitting. For octahedral complexes, crystal field splitting is denoted by Δo (or Δoct). The energies of the dz2 and dx2−y2 orbitals increase due to greater interactions with the ligands. The dxy, dxz, and dyz orbitals decrease with respect to this normal energy level and become more stable.

Description of d-Orbitals

To understand CFT, one must understand the description of the lobes:

- dxy: lobes lie in-between the x and the y axes.

- dxz: lobes lie in-between the x and the z axes.

- dyz: lobes lie in-between the y and the z axes.

- dx2-y2: lobes lie on the x and y axes.

- dz2: there are two lobes on the z axes and there is a donut shape ring that lies on the xy plane around the other two lobes.

Figure 3: Spatial arrangement of ligands in the an octahedral ligand field with respect to the five d-orbitals.

The electrons can go into either a high spin or low spin arrangement depending on the magnitude of the crystal field splitting energy.

High spin Low spin

The Spectrochemical Series:

The variation of the magnitude of the crystal field splitting (Δ) with the nature of the ligand follows a regular order, known as spectrochemical series. This series is given below in the order in which they produce increasing value of Δ.

I- < Br- < S22-< SCN- <Cl- < N3- < F- < urea, OH- < ox, O2- < H2O < NCS- < py, NH3 < en < bipy, phen < NO2- < CH3-, C6H5-< CN- <CO

- Weak field ligands have small Δ and will form high spin complexes.

- Strong field ligands have large Δ and will form low spin complexes.

Octahedral Complexes:

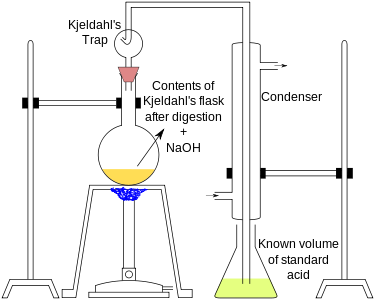

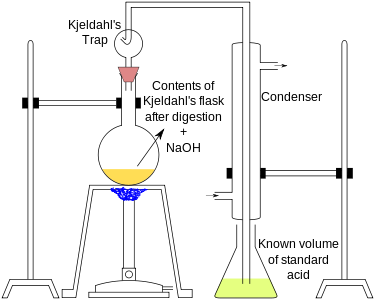

The octahedral arrangement of six ligands surrounding the central metal ion is as shown in the figure.

In an octahedral complex, the metal ion is at the centre and the ligands are at the six corners. In the figure, the directions x, y and z point to the three adjacent corners of the octahedran. The lobes of the eg orbitals (dx2-y2 and dz2) point along the x, y and z axis while the lobes of the t2g orbitals (dxy, dzx and dyz)point in between the axes. As a result, the approach of six ligands along the x, y z, -x,-y and –z directions will increase the energy of dx2-y2 and dz2 orbitals (which point towards the ligands) much more than that it increases the energy of dxy, dzx and dyz orbitals ( which point in between the metal-legand bond axis).

Thus, under the influence of an octahedral field, the d orbitals split into triply degenerate orbitals with less energy and another as doubly degenerate orbitals with higher energy. The main energy level between these two sets of orbitals is taken as zero, which is called bari centre. The splitting between these two orbitals is called crystal field splitting. The magnitude of stabilization will be 0.4 Δo and the magnitude of destabilization will be 0.6 Δo.

The magnitude of the splitting of the t2g and eg orbitals changes from one octahedral complex to another. It depends on the identity of the metal ion, the charge on this ion, and the nature of the ligands coordinated to the metal ion.

Tetrahedral Complex:

The tetrahedral arrangement of four ligands surrounding the metal ions is as shown in the figure.

A regular tetrahedron is a cube. One atom is at the centre of the cube and four of the eight corners of the cube are occupied by ligands. The directions x, y and z point to the face centres. The dx2-y2 and dz2 orbitals point along the x, y and z directions and dxy, dzx and dyz orbitals point in between x, y and z directions.

The direction of approach of ligands does not coincide exactly with either the e or t2 orbitals. The t2 orbitals are pointing close to the direction in which the e orbitals are lying in between the ligands. As a result, the energy of t2 orbitals increases compared to the energy of e orbitals. Thus, d orbitals again split into two sets- triply degenerate t2 of higher energy and doubly degenerate e orbitals of lower energy. That is, t2 orbitals are raised by 0.4 Δt in energy and the e orbitals are stabilized by 0.6 Δt in energy.

The energy difference between the two sets of orbitals (Δt) will be about half the magnitude of that in an octahedral complex (Δo).

Tetrahedral Complexes

In a tetrahedral complex, there are four ligands attached to the central metal. The d orbitals also split into two different energy levels. The top three consist of the dxy, dxz, and dyz orbitals. The bottom two consist of the dx2−y2 and dz2 orbitals. The reason for this is due to poor orbital overlap between the metal and the ligand orbitals. The orbitals are directed on the axes, while the ligands are not.

Figure 5: (a) Tetraheral ligand field surrounding a central transition metal (blue sphere). (b) Splitting of the degenerate d-orbitals (without a ligand field) due to an octahedral ligand field (left diagram) and the tetrahedral field (right diagram).

The difference in the splitting energy is tetrahedral splitting constant (Δt), which less than (Δo) for the same ligands:

Δt=0.44Δo(1)

Consequentially, Δt is typically smaller than the spin pairing energy, so tetrahedral complexes are usually high spin.

The d-orbitals will thus split as shown below:

Crystal Field Stabilization Energy:

The crystal field stabilization energy (CFSE) is the stability that results from placing a transition metal ion in the crystal field generated by a set of ligands. It arises due to the fact that when the d-orbitals are split in a ligand field (as described above), some of them become lower in energy than before with respect to a spherical field known as the bari centre in which all five d-orbitals are degenerate. For example, in an octahedral case, the t2g set becomes lower in energy than the orbitals in the bari centre. Owing to the splitting of the d orbitals in a complex, the system gains an extra stability due to the rearrangement of the d electrons filling in the d levels of lower energy. The consequent gain in bonding energy is known as crystal field stabilization energy (CFSE).

If the splitting of the d-orbitals in an octahedral field is Δoct, the three t2g orbitals are stabilized relative to the bari centre by 2/5 Δoct, and the eg orbitals are destabilized by 3/5 Δo.

For an octahedral complex, CFSE:

CSFE = - 0.4 x n(t2g) + 0.6 x n(eg) Δ0

Where, n(t2g) and n(eg) are the no. of electrons occupying the respective levels.

For a tetrahedral complex, CFSE:

The tetrahedral crystal field stabilization energy is calculated the same way as the octahedral crystal field stabilization energy. The magnitude of the tetrahedral splitting energy is only 4/9 of the octahedral splitting energy, or Δ t =4/9 Δ0.

CSFE = 0.4 x n(t2g) -0.6 x n(eg) Δt

Where, n(t2g) and n(eg) are the no. of electrons occupying the respective levels.

Square Planar Complexes

In a square planar, there are four ligands as well. However, the difference is that the electrons of the ligands are only attracted to the xy plane. Any orbital in the xy plane has a higher energy level. There are four different energy levels for the square planar (from the highest energy level to the lowest energy level): dx2-y2, dxy, dz2, and both dxz and dyz.

Figure 6: Splitting of the degenerate d-orbitals (without a ligand field) due to an square planar ligand field.

The splitting energy (from highest orbital to lowest orbital) is Δsp and tends to be larger then Δo

Δsp=1.74Δo(2)

Moreover, Δsp is also larger than the pairing energy, so the square planar complexes are usually low spin complexes.

A consequence of Crystal Field Theory is that the distribution of electrons in the d orbitals may lead to net stabilization (decrease in energy) of some complexes depending on the specific ligand field geometry and metal d-electron configurations. It is a simple matter to calculate this stabilization since all that is needed is the electron configuration and knowledge of the splitting patterns.

Table 1: Crystal Field Stabilization Energies (CFSE) for high and low spin octahedral complexes

| Total d-electrons | Isotropic Field | Octahedral Complex | Crystal Field Stabilization Energy |

|---|

| | | High Spin | Low Spin | |

|---|

| | Eisotropic field | configuration | Eligand field | configuration | Eligand field | High Spin | Low Spin |

|---|

| d0 | 0 | t2g0eg0 | 0 Δo | t2g0eg0 | 0 Δo | 0 Δo | 0 Δo |

| d1 | 0 | t2g1eg0 | -2/5 Δo | t2g1eg0 | -2/5 Δo | -2/5 Δo | -2/5 Δo |

| d2 | 0 | t2g2eg0 | -4/5 Δo | t2g2eg0 | -4/5 Δo | -4/5 Δo | -4/5 Δo |

| d3 | 0 | t2g3eg0 | -6/5 Δo | t2g3eg0 | -6/5 Δo | -6/5 Δo | -6/5 Δo |

| d4 | 0 | t2g3eg1 | -3/5 Δo | t2g4eg0 | -8/5 Δo + P | -3/5 Δo | -8/5 Δo + P |

| d5 | 0 | t2g3eg2 | 0 Δo | t2g5eg0 | -10/5 Δo + 2P | 0 Δo | -10/5 Δo + 2P |

| d6 | P | t2g4eg2 | -2/5 Δo + P | t2g6eg0 | -12/5 Δo + 3P | -2/5 Δo | -12/5 Δo + P |

| d7 | 2P | t2g5eg2 | -4/5 Δo + 2P | t2g6eg1 | -9/5 Δo + 3P | -4/5 Δo | -9/5 Δo + P |

| d8 | 3P | t2g6eg2 | -6/5 Δo + 3P | t2g6eg2 | -6/5 Δo + 3P | -6/5 Δo | -6/5 Δo |

| d9 | 4P | t2g6eg3 | -3/5 Δo + 4P | t2g6eg3 | -3/5 Δo + 4P | -3/5 Δo | -3/5 Δo |

| d10 | 5P | t2g6eg4 | 0 Δo + 5P | t2g6eg4 | 0 Δo + 5P | 0 | 0 |

P is the spin pairing energy and represents the energy required to pair up electrons within the same orbital. For a given metal ion P (pairing energy) is constant, but it does not vary with ligand and oxidation state of the metal ion).